In my recent model evaluations, one question keeps coming up: can a coding agent stay fast, reliable, and affordable when tasks involve multi-file edits, repeated debugging, and tool use—not just single-turn answers? MiniMax M2.5 is one of the few releases that ships with enough end-to-end efficiency and pricing detail to test that question in a concrete way.

Why I’m Paying Attention to M2.5

I focus less on “one best benchmark score” and more on whether a model can complete real workflows:

- End-to-end delivery: scope → implementation → validation → deliverables

- Operational efficiency: tool-call iterations, token use, and runtime stability

- Agent economics: whether the pricing model supports long-running agents and repeated iterations

MiniMax M2.5 is interesting because it aims to optimize capability, efficiency, and cost in the same release—an important combination for engineering teams making deployment decisions.

What M2.5 Is Built For

Based on the official materials, MiniMax M2.5 is positioned for real-world productivity workloads across three main tracks:

- For Software Engineering (Agentic Coding): represented by SWE-Bench Verified, Multi-SWE-Bench, and an emphasis on stable performance across different harnesses.

- For Interactive Search and Tool Use: including BrowseComp, Wide Search, and MiniMax’s in-house RISE benchmark designed to reflect deeper exploration within professional web sources.

- For Office Productivity: focused on deliverable-oriented tasks in Word, PowerPoint, and Excel, supported by an evaluation framework (GDPval-MM) that considers output quality, agent execution traces, and token cost.

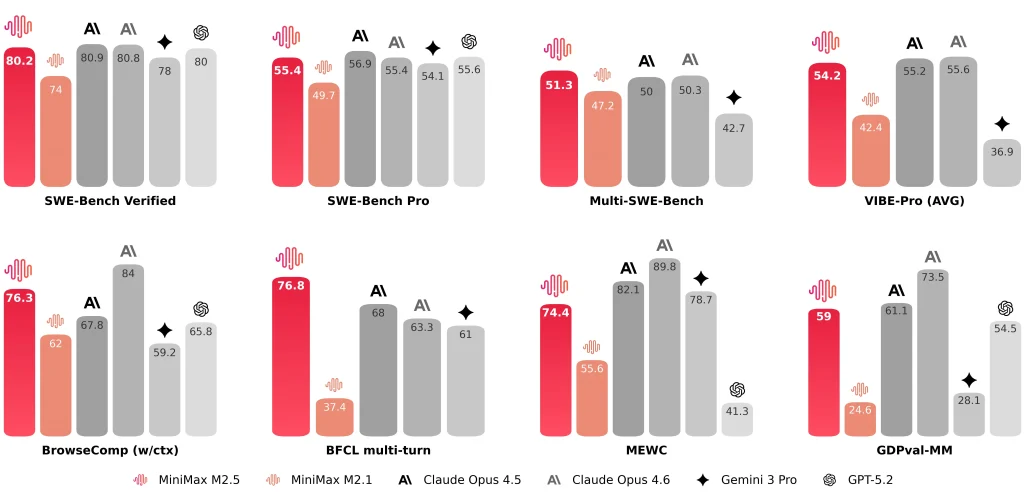

MiniMax also discloses representative results such as SWE-Bench Verified 80.2%, Multi-SWE-Bench 51.3%, and BrowseComp 76.3%.

MiniMax M2.5 vs M2.1 and Claude Opus 4.6: What I Compare

M2.5 vs M2.1 vs Claude Opus 4.6 (Key Metrics Table)

| Dimension | M2.5 | M2.1 | Claude Opus 4.6 |

| SWE-Bench Verified | 80.20% | 74.0% | 81.42% (Anthropic reported) ~78-80% (Public avg) |

| Avg. end-to-end time per SWE task | 22.8 min | 31.3 min | 22.9 min |

| Tokens per SWE task (avg.) | 3.52M | 3.72M | — (Likely >4M due to verbosity) |

| Search/tool iterations vs prior gen | ~20% fewer iterations (reported) | Baseline | — |

| Cross-harness SWE-Bench (Droid) | 79.7 | 71.3 | 78.9 |

| Cross-harness SWE-Bench (OpenCode) | 76.1 | 72.0 | 75.9 |

| Throughput options | ~50 tokens/s (standard) ~100 tokens/s (Lightning) | ~57 tokens/s | ~67-77 tokens/s |

| Pricing (per 1M input tokens) | $0.3 (standard & Lightning) | $0.3 | $5.0 |

| Pricing (per 1M output tokens) | $1.2 (standard) $2.4 (Lightning) | $1.2 | $25.0 |

| Hourly intuition (continuous output) | ~$0.3/hr @ 50 t/s ~$1/hr @ 100 t/s | ~$0.3/hr @ 57 t/s | ~$6.50/hr @ 70 t/s |

Notes:

- “—” means the value was not provided in the materials summarized here.

- Benchmarks can differ by harness, tool setup, prompts, and reporting conventions, so I treat them as range indicators, not absolute rankings.

M2.5 vs M2.1: Faster End-to-End, Lower Token Use, Fewer Search Iterations

The official comparison is presented in an engineering-friendly way. I pay attention to three specific metrics:

- End-to-end runtime: average SWE task time drops from 31.3 minutes (M2.1) to 22.8 minutes (M2.5), described as a 37% improvement.

- Tokens per task: token usage per task decreases from 3.72M to 3.52M.

- Search/tool iteration efficiency: on BrowseComp, Wide Search, and RISE, MiniMax reports better outcomes with fewer iterations, with iteration cost roughly 20% lower than M2.1.

For me, these improvements matter more than a single benchmark score because they directly determine agent throughput and sustainable operating cost.

M2.5 vs Claude Opus 4.6: Similar Coding Range, Evaluation Context Matters

When comparing M2.5 with Claude Opus 4.6, I treat scores as ranges rather than absolute rankings, because harnesses, tool configurations, prompts, and reporting conventions can differ.

- Anthropic notes that Opus 4.6’s SWE-bench Verified result is an average over 25 trials, and mentions a higher observed value (81.42%) under prompt adjustments.

- MiniMax reports SWE-Bench Verified 80.2% for MiniMax M2.5.

Numerically, the two appear to sit in a similar competitive band for coding-agent benchmarks. From an engineering perspective, I care more about stability across real project shapes—front-end + back-end, different scaffolds, and third-party integrations—than about a single headline number.

How M2.5 Changes My Workflow (Hands-On Notes)

Speed and Workflow Style

After integrating MiniMax M2.5 into a coding-agent toolchain, two things stand out:

- MiniMax M2.5 speed materially improves short-task iteration. Many real tasks follow the loop “small change → run → adjust.” If each loop introduces long waits, context switching becomes costly. MiniMax explicitly highlights “faster end-to-end” and “lower token use” as core outcomes.

- MiniMax M2.5 tends to write a Spec before implementation. For multi-file and multi-module tasks, I prefer the model to explicitly capture scope boundaries, module relationships, and acceptance criteria before writing code. This makes execution easier to audit and standardize, and M2.5 performs well under this structure.

These Points shouldn’t be Overlooked

Even with strong overall performance, I still treat the following as constraints that need workflow guardrails:

- Debugging strategy is not always proactive: for hard-to-localize bugs, the model may repeatedly modify implementation without automatically switching to unit tests, logging, or minimal repro steps. I often need to explicitly instruct: “add logs / write tests / narrow down the failing path.”

- External retrieval and third-party integration can be unreliable: when integrating certain external services, the model may produce incorrect integration steps. I prefer to constrain inputs with official documentation examples instead of relying on “retrieval-assembled” code.

- Code-and-docs synchronization is not consistently default: when a task requires “update code and also update the documentation/Skill markdown,” I use an explicit checklist to reduce the chance that only code gets updated.

These constraints are not unique to M2.5; they are guardrails I apply to most coding-agent workflows.

At this stage, I position MiniMax M2.5 as an engineering-oriented agentic productivity model. It does not only provide benchmark results; it also discloses end-to-end runtime, token consumption, iteration efficiency, and pricing structure, which allows me to evaluate real deployment cost using a consistent set of metrics.

Some users may question whether generating a Spec before coding increases token cost and undermines the “low cost” claim. My practical conclusion is:

- Yes, writing a Spec adds some output tokens.

- In many real workflows, that cost is offset by fewer rework loops and fewer back-and-forth iterations, especially for multi-file, cross-module, or debugging-heavy tasks.

- The overhead is usually controllable as long as the Spec is not excessively long and does not repeat implementation details.

Here are Some Practical Tips to Minimize Spec Token Overhead:

- For small tasks: explicitly request “no Spec; provide a code diff plus test steps.”

- For medium/large tasks: constrain the Spec to X lines / X bullets (e.g., 10–15), focusing only on structure and acceptance criteria, not implementation details.

- In agent toolchains: treat the Spec as the single source of truth. Update the relevant Spec section first when requirements change, then proceed to coding and validation. This reduces repeated explanations and hidden token waste from re-stating context.